The Emperor Honorius, son of Theodosius I, moved the capital from Milan to Ravenna in 402; in the words of Edward Gibbon, to remove himself from the tribulations of the risky business of being Emperor, with Ravenna more or less impregnable and quite out of the way of the primary activities of empire during a period of turmoil. Furthermore, for the barbarian generals, having the emperor out of the way, meant they would have a far freer hand in their military activities. Seemingly, this was an arrangement suitable both for emperor and general, but in reality was another symptom of the continued decline of the Western Empire.

With the sack of Rome by Alaric’s Visigoths in 410, Galla Placidia, a daughter of Theodosius I and half-sister to Honorius, was taken hostage. Despite this, the Visigoths would forge an alliance with the emperor a couple of years later and Galla Placidia would marry Alanathus (the successor to Alaric). The Goths would go on to defeat two pretenders to the throne in Gaul, and settle in the area of today’s Provence. With the death of Alanathus, Galla Placidia would eventually return to Ravenna, living there for the remainder of her life as regent to the young Valentinian during his minority. Surviving a rough sea voyage, she was to commission the construction of the San Giovanni Evangelista basilica. While most of the original mosiacs here have been destroyed, some of the fragments that remain are these two, very much in the tradition of Roman mosaics.

Galla Placidia’s Mausoleum is described as “the earliest and best preserved of all the mosiac monuments…” by UNESCO. The mosaics are wonderful, with their theme of night and day, and their detailed imagery, but what caught my eye the most were two panels of thinly shaved semi-precious stone, that filtered the light into an otherwise dim interior.

The amber colouring of these panels seem to presage the introduction of the golden mosaics that were essentially to define Byzantine mosaics for centuries to come, and the sense of creating an atmosphere of a “heavenly light” as a part of the purpose of the art works.

With the fall of the Western Empire in 476, the Ostrogoths would rule most of the Italian Peninsula from Ravenna. The Ostrogoths (as with the Visigoths) were adherents of the Arian heresy. Heresy and the general contentiousness of theological orthodoxy were to consume vast swathes of time, lives through persecution, and resources throughout the course of Christian history. As Christianity emerges as the official religion of the Empire, the division of the church into heresies and orthodoxy are apparent. Essentially, it is a problem of “one God, one church, one empire”, but then you have to define what that “one” doctrine is. The Arian heresy, one of the first of the major divisions, placed Christ, the Son, as inferior to, a created being by, God the Father and was to deny the essential doctrine of the trinity of orthodox Christianity.

During their tenure as rulers in Ravenna, the Ostrogoths were to build two Baptisteries that housed Mosaics of the same composition; the Arian Baptistry of Santa Maria (built by Theodoric)

and this image from the Baptistry attached to the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo.

To see the depiction of Christ’s “full raiment” (shall we say) was quite notable! You see the humanity of Jesus and is a remarkably fresh image on any number of grounds; my thoughts went to the rows of oak leaves covering up the genitalia of classic statues within the Vatican, the typically “above human” elevation, the a-sexual portrayal, of leading religious figures. And here we have Jesus, un-ashamably portrayed as a natural human.

This baptistery dates from 504, and I think the mosaics in this (and the other Baptistery) are one of the first uses of the golden background in Christian art (along with the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, built in the 530s). With the subject of these mosaics, the gold seems to not only represent the splendour of the devotional images, not only to reflect and create a golden light, the “Light of Heaven”, but also is an expression of the transcendent God, the true “One God”, of the Arian heresy. Christ and the Holy Spirit are as illustrated as figures, created and of the world. The gold background was to become a defining feature of Christian religious art for hundreds of years to come, right up until the early Renaissance.

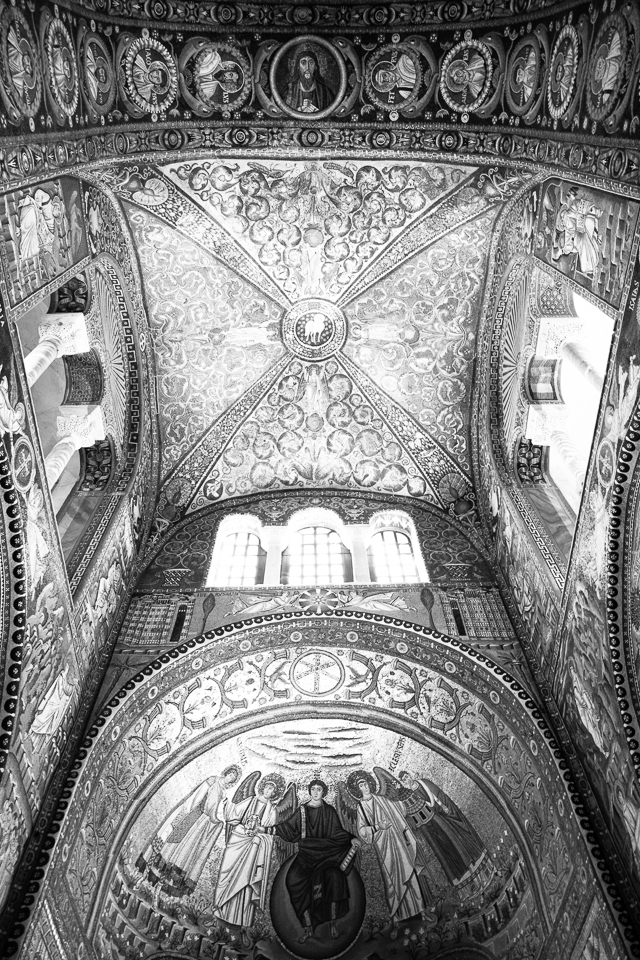

The Basilica of San Vitale is one of the most significant repositories of Byzantine mosaics remaining to us. It was begun in 526 by the Ostrogoths. The Byzantines, under the great General Belisarius, would conquer much of the Italian Peninsula and entered Ravenna in 540. The cathedral was completed in 547, including modifications from the Byzantines, and the addition of the most famous mosaics depicting the Emperor Justinian and the Empress Theodora.